Saturday, October 10, 2015

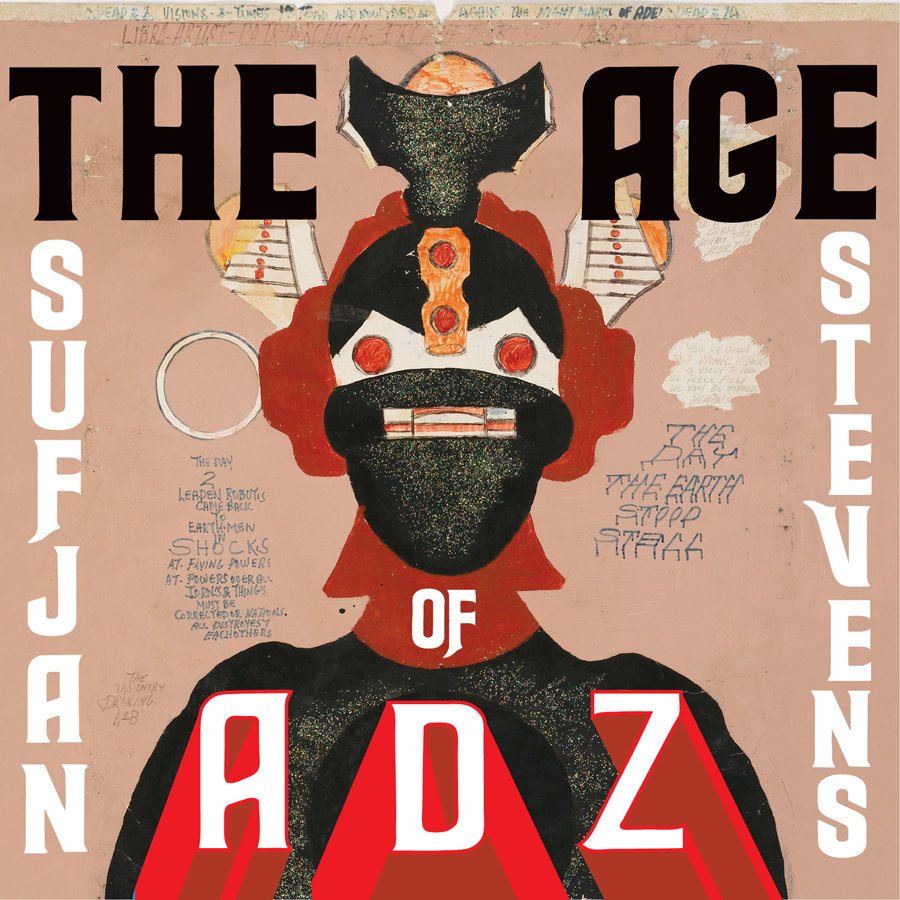

the age of adz

Sufjan Stevens found healing in the transformative power of extraordinary ordinary things through a primal cacophonous expression of the language of ghosts, eternal living, and impossible soul. It had been five years since he had his breakthrough with his celebrated concept album 'Illinois' in 2005, and in the interim Stevens had taken a hiatus from recording. The success of the album and the scope of the expectations it put on him were like an albatross around his neck. He put out odds and ends in the form of The Avalanche B-sides collection and the five EP Songs for Christmas box set in 2006. In 2007, he became involved with The BQE , an audio-visual art project about the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway that changed him profoundly. Stevens reveals: "I think I just got fed up with my own existential quandary, and got really bored with this sort of circular, philosophical pondering and my obsession with naming things and categorizing things. I think I wasn’t so much [disillusioned] with songwriting as I was disillusioned with form, and I was really frustrated with the limitations of the song. And I think a lot of that was suffering the repercussions of The BQE and having spent way too much time investing in that project and trying to render something meaningful out of this ugly modern urban expressway. And I really wanted to challenge the form, the format of the song. And that piece, by making it a film, and making it a soundtrack, and making it a photo-essay and exposition, and everything else except for song…when it was all finished I realized that I felt really sort of creatively spent but unsatisfied, you know? It made me really question, well what is a song? Why are we so limited by these parameters? And then at some point I just got fed up with the kind of whiny, existential questioning, and I realized that really wasn’t my business to differentiate these categories, that my role was to do the best work possible, and not try to categorize it beforehand. I also got really sick, and you know, and couldn’t write for a while, cause I went through all this crazy physical stuff, and then when I came out of that, I sort of felt kind of this necessary revitalization, and I just felt like I had a second lease on life. I was really excited about writing—didn’t even want to question it anymore ... It signalled a big sea-change for me in terms of my process...[The BQE] kinda sabotaged the mechanical way of approaching my music, which was basically narrative long-form. It really opened things up for me. It also confused things as well. I don’t think I ever really fully recovered from that process...I think I was getting tired with myself. My voice was really starting to get on my nerves...I think it’s really good for me. It was such a relief to just write a song on instinct and allow myself to be impulsive...I think the enforced conceptual boundaries are really healthy and helpful, but they can be restrictive and can hinder exploration...I love denying myself the fundamental tools of the trade. I love giving myself obstacles. It feels like starting over. It never really gets old.”

In 2009 he began recording again, releasing Run Rabbit Run, a reworking with strings of his electronic album from 2001 Enjoy Your Rabbit, which indicated a return to that aesthetic. The All Delighted People EP was released online in August of 2010 and 'The Age of Adz' followed in October. The music was more primal and expressive and was a shock to his new fans who were only familiar with the folky narratives of 'Illinois'.

Stevens admits: "I was aware that the textures and the sonic environment was a little dirtier, more cacophonous, or whatever. I was aware of that, cause I feel like I was also extremely aware during the making of Illinois of how much effort I put into making it listenable. It’s such a populist record—there’s just so much effort in appealing to the listener, you know there’s such a kind of a pageant of sound, and it’s constantly entertaining and rewarding, and it’s just sort of a patchwork of this sort of harmonic beauty, harmonic what do you call it, I don’t know—It’s very harmonious. You know, The Age of Adz, these are pop songs, but they’re based on sound experimentation and noise. They’re more aggressive, and even my tone of—the way I’m singing—it’s more in my throat and not always pretty. So I was aware of that, and I just felt like an imperative to experiment with these tones, and generally, I think now more than ever, I’m making music for that elite 5%—you know, the listener who’s been with me from the very beginning and understands my interest in electronic music and noise and in sound sculpting and minimalism and all that stuff. So I think that that record, The Age of Adz, is really for that listener, you know? I don’t think it’s meant to be for the casual listener who likes the song “Chicago,” which is fine. There’s no condescension at all in that remark. I don’t condescend to any of my music or to any listener. But I just am not in a season right now of feeling that kind of populist thrust. I don’t feel motivated to make things so listenable.

During this creative upheaval, Stevens fell prey to an unspecified nervous disorder that manifested in lethargy, painful sensations all over his body, adrenaline surges, and hypersensitivity. He recalls: "This was really supernatural. It was like I was possessed ... For several months, I couldn't really work and was forced to focus on my physicality and restoring myself. It took several months before I could even get back to working again and writing music."

The tormented work of paranoid schizophrenic artist Prophet Royal Robertson seemed to help Stevens work through his pain and coalesce the edgy music he was creating for his next album that had become, as he says, "really monstrous and hazardous in its ambition ... I was really, really desperate to get better because I had started so much music; I had begun all of these projects and was recording a lot. Then when I went back to it, I found it really overwhelming and I didn't know how to approach it. So, this record, The Age of Adz, is, in some ways, a result of that process of working through health issues and getting much more in touch with my physical self. That's why I think the record's really obsessed with sensation and has a hysterical melodrama to it."

The album drew its title from one of Robertson's pieces, and most of the artwork on the album was taken from pieces done by Robertson.

Stevens expounds: "I can't apologize for the direction I'm going because it feels necessary and obvious. I know it's confusing because I'm something of an aesthetic nightmare, and I kind of suffer from multiple personality disorder. But that's part of me and my character. So, I guess I don't care. It's a big shift, and it may not be for some people. They should stay home. [laughs] Don't listen to the record; don't buy it. I'm very aware that this material is far less popular and accessible than the kind of songwriting on Illinois. I'm also willing to admit that these songs don't measure up to the songs I was writing five years ago; these aren't great songs in terms of the palpable, fundamental nature of a song. But I'm not interested in songwriting anymore. I'm interested in sound and movement. And this material is all about that. Unfortunately, we sold the tickets to the tour before I even had the record done, so a lot of people didn't really have the chance to know what they were investing in. I apologize for that...Life is all about toiling and labor. But obviously I get great joy in confronting challenge and taking risk. I don't ever want to be comfortable...I have a hard time distinguishing what is valuable when it comes to the real world and the fantasy world. Like, should I invest my time in the ordinary world or the imaginary world? Royal made a decision and completely escaped the ordinary world. Maybe that's enlightenment. Maybe that's what it's like to be in heaven. I don't know...For me, the sensory pleasure of sound and music is so transcendent that I begin to distrust it and worry if it's a distraction from ordinary life. Maybe I should be spending my time doing something else, like start a family. Or build an amusement park-- actually, that's still a fantasy world. Engineering? Investment banking? Real estate? There are all kinds of people who make the world go 'round. [laughs]...I wanted to be a graphic designer, a teacher, a writer. We all have our plans, but they're worth nothing. There's a sequence of events that takes over. But I'm not quitting now. I'm fully embracing the life of the musician...I'm less interested in songwriting and more into just making noise."

'The Age of Adz' reached number sixty-one in Australia, thirty in the UK, twenty-three in Ireland, thirteen in Canada, and became his highest charting album at number seven in the US. Stevens considers: "I went through a period of questioning motive and function and now I no longer have the privilege of questioning. I just have the privilege of celebrating my music and sharing it. I don't really want to get caught up in that self-doubt any more. I've always been really insecure about what I do, but those existential conundrums are really circuitous and – what's the word? – unproductive. You know, I don't think my music is important, I don't think it's changing the world, I don't think it's art. I just think it's music. It is what it is."

http://music.sufjan.com/

lyrics:

http://genius.com/albums/Sufjan-stevens/The-age-of-adz

"Too Much"

"Get Real Get Right"

"All For Myself"

'The Age of Adz'

full album:

http://music.sufjan.com/album/the-age-of-adz

https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLZqsyBiYZFQ2aB-JyI-J1-tyxaD-73TSa

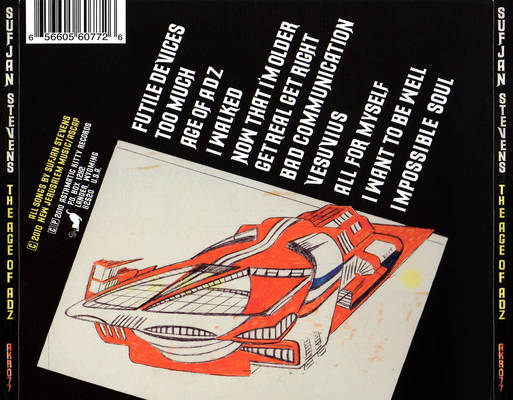

All songs written and composed by Sufjan Stevens.

1. "Futile Devices" 2:11

2. "Too Much" 6:44

3. "Age of Adz" 8:00

4. "I Walked" 5:01

5. "Now That I'm Older" 4:56

6. "Get Real Get Right" 5:10

7. "Bad Communication" 2:24

8. "Vesuvius" 5:26

9. "All for Myself" 2:55

10. "I Want to Be Well" 6:27

11. "Impossible Soul" 25:35

Total length: 74:49

No comments:

Post a Comment